Heaven for Atheists

When I was seventeen, my boyfriend at the time, Jon, showed me a movie he and his friends had made about the cryogenically frozen head of Walt Disney. The plot revolved around the evil high jinks of the reanimated (and still disembodied) head of the Mickey Mouse creator. I laughed and asked whether Disney’s head really was frozen. Jon contended it was. The next question was, naturally, why would anyone choose to freeze themselves, let alone just their head? I don’t remember his answer, and it’s likely things had dissolved into making out by that point.

I filed it away along with the other useless bits of information I acquired in high school until this past summer, when my thoughts were furthest away from frozen bodies and my current boyfriend, Larkin, asked me what I thought of cryonics.

“You mean, like the cryogenically frozen head of Walt Disney?” I said, feeling clever for being able to recall the urban legend I’d learned about twelve years prior.

“Cryonics,” he insisted. “And I’m not sure Disney’s head really is cryonically frozen.” (It isn’t.)

Not wanting to appear ignorant, I waited until Larkin left and turned to my trusted source, Wikipedia, to find out the difference between cryonics and cryogenics. Cryogenics, I learned, is “the study of very low temperatures… and how materials behave at those temperatures,” and cryonics is the “emerging medical technology of cryopreserving humans and animals with the intention of future revival.” (So, a square is a rectangle, but a rectangle is not a square.) I would also discover that there are people for whom this isn’t a science fiction but rather a real possibility for preserving life, perhaps even a way to achieve immortality.

To understand how this might work, one first must realize that our bodies are not operated by an “on and off” switch, meaning that when you die, you don’t necessarily die instantaneously. This shouldn’t be so hard to accept since we’ve all heard examples of people declared legally dead before miraculous (read: defibrillator-enabled) revival. So the “switch” is more like a dimmer. It takes four to six minutes (perhaps as long as ten minutes or up to almost an hour, depending on what source you believe) for the brain to suffocate from lack of oxygen and stop functioning. Now imagine that a human could be captured in that time after the heart stops and before the brain starts to degrade and that he or she could be suspended in this state indefinitely, like hitting pause on the dying process. Let’s say that, hypothetically, the body (or at least the brain) could be revived from that state (“unpaused”) at a time of more advanced technology, a time when the person could be treated for whatever caused the body to start shutting down in the first place—cancer, for example. And if such technology existed, then (in the case where the head is the only thing preserved), the technology for regrowing the body for the brain (or at the very least, creating a bionic one) should reasonably exist as well.

That, in a nutshell, is cryonics.

I thought Larkin was perhaps a bit insane—or at least unreasonably hopeful—the first time he explained this to me. It was a real way to live forever as far as he was concerned, and he wanted my thoughts on it. My thoughts were that he seemed obsessed with aging and death, as evidenced by his daily SPF 50 sunblock slathering, even on winter days when he knew he wouldn’t be out in the biting Minnesota cold for more than ten minutes. My thoughts were that the six-year age gap between us was starting to get to him, maybe because the last time we went to a bar together, I was carded and he wasn’t.

It took a few weeks for my boyfriend’s seriousness about the whole cryonics thing to sink in. He emailed me links to articles, talked endlessly about mind uploading (“backing up” our brains on computers) and about nanobots injected into our bloodstreams, the miniature robots programmed to rid our bodies of all the bad stuff. I started to worry his fixation was a glimpse into my own future obsession. I’m still (though marginally) in my twenties and able to wave away most of the concerns, but perhaps I’ll change my mind when I hit my thirties. I see where it’s started to take root: already I’ve begun to subscribe to what two years earlier I’d described as a friend’s unhealthy addiction to $90 eye cream. Who’s to say I won’t be in Larkin’s exact spot six years from now, if not sooner?

It’s human nature, I suppose, to want to survive, to resist succumbing to the same fate all living things do. It’s the reason we write books, create art, have children—we’re hardwired to want to leave a legacy. Many even invent afterlives, rarely accepting death at face value but instead saying that someone who’s died has “gone on to a better place.” Some don’t even call it death but rather feel the need to be polite in saying someone “passed away.” These are the comforts we afford ourselves so we don’t have to confront the inevitable. Cryonics, I have decided, is an afterlife for atheists.

And like all atheists, I approach this science-fiction afterlife with skepticism. I can be persuaded, of course, but with evidence. So I set out to do a bit of research into a company whose name I’ve heard Larkin throwing around a lot lately: Alcor.

Perhaps this name sounds familiar. “Is that the place where they used that baseball player’s head to play croquet?” you ask. Well, yes and no. Alcor did face allegations that its employees used former baseball great Ted Williams’ head for batting practice (also using a wrench to indelicately remove a can that had become frozen to it), but the accusations seem to be contained just within the pages of former Alcor employee Larry Johnson’s book, Frozen;though denials of said accusations also seem to be advertised in just one source: Alcor’s website. Best I can tell from my hour of Internet digging, the actual circumstances of the Ted Williams affair and Alcor ethics in general are perhaps a “he said, she said”/yellow journalism sort of situation, the actual truths of which cannot easily be discerned. But what I’m really after is why Ted Williams froze his head in the first place: Is cryonics even possible? Or are its believers just as hopelessly optimistic about escaping death as their religious counterparts?

Alcor, a nonprofit leader in cryonics, has maintained its “life extension” site outside of Phoenix, Arizona, since 1972. It’s the mainstay of the cryonics world, and, along with a few other for-profit cryonics organizations, seem to be the only source of information on the matter—there’s just not much science out there about cryonics. So, though it’s biased, I decide to begin my search for the answers to my questions at Alcor’s website (www.alcor.org).

I head right to the Cryonic Myths section, figuring I might as well cut to the chase. I start with Myth #2 (saving #1, “Cryonics Is Consumer,” for later). Myth #2 covers perhaps the most commonly misunderstood part of cryonics, which is that cryonics freezes people. In actuality, cryonics is achieved through vitrification. This differs from freezing in that 60 percent of the water inside the cells is replaced with protective chemicals called cryoprotectants before the temperature is dropped. Instead of freezing, the body’s molecules slow movement until all chemical reactions stop (at approximately -124°C). If cryonics were simply freezing, ice crystals would form and damage the tissue. If you’ve ever frozen a banana and then tried thawing it out, you know it doesn’t rebound to its natural banana shape. This is because the formation of ice crystals (freezing) and subsequent deformation (thawing) cause changes in the molecules. However, while vitrification ensures there is no damage due to ice-crystal formation, reversing the process does not yet work quite the way cryonics is intended—the vitrification solution itself has some biochemical side effects.

I head right to the Cryonic Myths section, figuring I might as well cut to the chase. I start with Myth #2 (saving #1, “Cryonics Is Consumer,” for later). Myth #2 covers perhaps the most commonly misunderstood part of cryonics, which is that cryonics freezes people. In actuality, cryonics is achieved through vitrification. This differs from freezing in that 60 percent of the water inside the cells is replaced with protective chemicals called cryoprotectants before the temperature is dropped. Instead of freezing, the body’s molecules slow movement until all chemical reactions stop (at approximately -124°C). If cryonics were simply freezing, ice crystals would form and damage the tissue. If you’ve ever frozen a banana and then tried thawing it out, you know it doesn’t rebound to its natural banana shape. This is because the formation of ice crystals (freezing) and subsequent deformation (thawing) cause changes in the molecules. However, while vitrification ensures there is no damage due to ice-crystal formation, reversing the process does not yet work quite the way cryonics is intended—the vitrification solution itself has some biochemical side effects.

My mother always encouraged me to make a pros-and-cons list whenever I had a difficult decision to make, so I start a scorecard for cryonics. On the pro side I write, “+1: vitrification over freezing.” I pause and consider, then jump to the con side: “-1: vitrification working only as a one-way street to Frozenville.” I put down the pen and keep reading.

Myth #3 explains how cryonics isn’t revival of the dead but rather “a belief that no one is really dead until the information content of the brain is lost, and that low temperatures can prevent this loss.” Alcor acknowledges that reversibility of this process will not be available for decades to come, but in the meantime, they say cryonics patients are in life suspension, merely unconscious. They state that “life is often mistaken for death when resuscitation methods are not sufficiently advanced.” Reading this, I can’t help but think of a Tales from the Crypt episode where a guy gets buried alive. Still, this doesn’t seem like a point-earning or -deducting situation (it’s only bad in that I was reminded of the Crypt Keeper and that disturbing episode), so no points lost or gained for cryonics here.

Myths 4 and 5 seem to go hand-in-hand, as they both cover the greater scientific community’s consensus on cryonics. Alcor contends that most scientists say cryonics can’t work because they simply don’t know how it does. Cryonists at Alcor argue that most of the science community is ignorant of vitrification, and that without the knowledge of how vitrification works for the preservation of organs (in practice, that is, not just theoretically), then of course cryonics would seem impossible. Vitrification is the lynch pin to it all. I can’t really find anything that discusses cryonics scientifically other than cryonics sites where cryonics is for sale, so it’s difficult to determine what the scientific community really thinks. Are they not saying anything because it’s not worth acknowledging a science fiction? After all, you likewise won’t see articles by scientists denying the existence of the Tooth Fairy. Again, no points gained or lost.

Myth #6, that cryonics preserves heads, is somewhat true. It is most effective (and cost efficient) for just the head of a patient to be vitrified, so yes, oftentimes cryonics focuses on just the head, the idea being that the important part of the person, what makes someone who (s)he is, is contained within the brain; a new body can be given to house the brain. I see this point and would like to add something Alcor doesn’t highlight, which is that if I were to invest in cryonics and died at an older (eighty-something) age and were revived, I would most likely welcome being given a new, non-eighty-something body. Cryonics: +1.

Myth #7, “Cryonics Conflicts with Religion,” seems unlikely, as those who believe in an all-perfect heaven would most likely prefer just to die and go there rather than keep their fingers crossed for the all-perfect reanimation, the odds of which are much dicier. There are perhaps some exceptions to that rule, though, and for those, Alcor assures that there are no competing interests between cryonics and religion—it’s like saying there’s a religious reason not to keep a comatose person on life support because the life-sustaining measures go against God’s wishes/keep the person from going to heaven. (And if you’re of this religious variety, again you won’t be investing in cryonics anyway.) I’m not religious, so #7 has no bearing on me. No points gained or lost.

Myth #8, “Cryonics Is an Indulgence of Rich People,” and Myth #1, “Cryonics Is Consumer Fraud,” seem best addressed together. Alcor assures people that cryonics is quite affordable, as they accept life insurance. They say they are not scamming grieving families by giving them false hope, instead noting that their primary interest is in “attracting young and healthy people to join Alcor and help build the cryonics field.” This, to me, does not allay the worry nor dispel the myth. Of course they’re interested in the young and healthy—so is anyone else who charges annual dues. If you’re young and healthy instead of old and on death’s door (when you’re actually ready to invest hope in the possibility of rising from the dead), you’ll end up throwing a lot more money their way. Tsk-tsk, Alcor, for your slippery logic. Cryonics: -1.

I add up the tally and see we’re at Cryonics: 0. And just in time for the final myth, “Cryonics Is Motivated by an Irrational Fear of Death.” Perhaps this is where I should’ve started, as my concern that my boyfriend is irrationally afraid of death (or, rather, obsessed with not dying) is what spurred me into this dissection of cryonics in the first place. Alcor states that it’s not irrational to want to avoid death, and if it is, why bother prolonging life in other ways?

I add up the tally and see we’re at Cryonics: 0. And just in time for the final myth, “Cryonics Is Motivated by an Irrational Fear of Death.” Perhaps this is where I should’ve started, as my concern that my boyfriend is irrationally afraid of death (or, rather, obsessed with not dying) is what spurred me into this dissection of cryonics in the first place. Alcor states that it’s not irrational to want to avoid death, and if it is, why bother prolonging life in other ways?

This makes all too much sense to me. If you don’t have to worry about your body becoming decrepit (if cryonics works, and you can get a new, better, younger body), then why wouldn’t you want to live a much longer life? Don’t people generally lose the will to live just because it’s too physically painful, because their bodies give out on them? Admittedly, there’s still something creepy about the whole process, whether it’s capable of working or not (and perhaps more so if it is).

Most of the people I’ve talked to about cryonics find it perverse. They say they’d rather grow old gracefully and die like you’re supposed to, even the atheists. I get not wanting to be frozen—heck, even Larkin doesn’t want to be frozen—but is it worth it for the chance at living forever?

“Live forever? That sounds awful.” That from my mother and aunt, to which my aunt adds, “I’m not all that excited about living now. Why would I want to live forever?” My poor aunt’s depressed and some days seems like she’d be content being hit by a bus. M y mom, though initially bored with her retirement, keeps herself busy with various part-time jobs and house projects, so she’s of much more sound mind, it seems. “You wouldn’t want to live forever?” I ask her.

“Look at all those vampire movies,” she responds, as if using a fictional archetype to illustrate her point here is perfectly valid. “They’re always depressed and wishing they could die, and that’s after just a few hundred years. Imagine if it were longer than that. Plus you wouldn’t have any friends or family.”

I tell her they could get cryopreserved as well. “Then what do you think?”

She mulls this over for a bit then looks to her sister before answering, knowing there’s at least one person who wouldn’t be in that future. “No,” she decides, “I wouldn’t want to live forever.”

Next I turn to my best friend from college, Buck, thinking he’ll set me straight on the craziness of cryonics. Because I feel myself starting to agree with this life-preservation idea too much and have started what I call hypothetical worrying, in this case making plans around what I’d do if I woke up in a time a hundred years after my death, how I’d deal with the culture shock and the general logistics of living in a time not my own. I want someone to reaffirm my initial impression and reground me in the fact that one day, just like everyone before and after me, I am going to die. Buck surprises me by telling me he believes cryonics can work and is actually considering investing in it. His only real fear is about human hubris.

“What happens when we think we can do anything but find out we’re wrong?” he asks me. “Say scientists think they have reversibility figured out for cryonics, and they start reanimating the sleeping corpses and heads at the cryopreservation facilities. What if they’re wrong, or half wrong?”

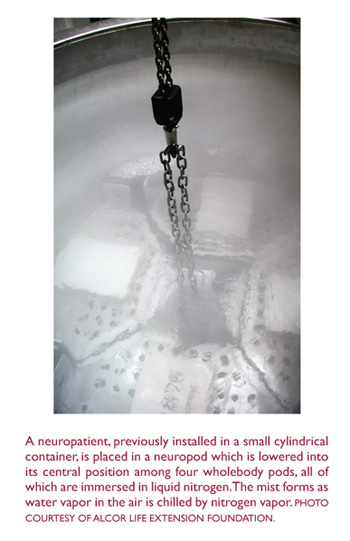

I consider this. My friend isn’t talking about a zombie apocalypse of the recently thawed. He’s more worried about the synapse-level damage that seems all too possible. I think about how tentative the balance of our brains is. All you need is one minor head injury to totally alter your personality. What happens when you put the brain into circumstances it doesn’t naturally have to deal with—temperatures so cold, no chemical activity can take place—and then try to bring it back into normal conditions? Could you potentially become brain damaged? Under whose charge would you then be if you were unable to take care of yourself? Does Alcor have a living-assistance fund set up for just such an occasion? And, worse yet, would there be a Flowers for Algernon moment where you realized your own diminished abilities?

Let’s say it does work with no negative side effects. Still, there are other questions. Why would they want to revive you anyway? After all, if we continue down the path of global abuse we’ve been on since the Industrial Revolution, there won’t be many resources available in the future. Future humans won’t want to revive you because you’ll be competition. Not that you want to awake to a Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome reality anyway.

I bring these questions to Larkin’s attention, and he has an answer for them all: “If it’s the not-so-distant future, your friends and relatives would want to revive you; if it’s the distant future, people of that time would be interested in people of our time, and if they’re able to revive us somewhat easily, why not? It’s only about a thousand people who are signed up for cryonics or are currently cryopreserved anyway. Plus at a certain point, it’ll be more cost effective to revive us than keep us frozen.” (I note here how he keeps including me in on this venture—us. I used to find this cute and liked how he referred to the two of us as a unit, but I’m not so sure I want Larkin signing me up to pay to become a popsicle; he appears to want to save some money with Alcor’s “family discount.”)

“And if it really is all ‘Mad Max,’ as you say, they’re not going to revive us anyway,” Larkin continues. “But what would we care that we spent the money and it didn’t happen? We’re dead. It’s not like we’d know the difference.”

Larkin understands it’s a crapshoot, but he likes the odds of “better than zero” better than none. Then he reassures me: “This is probably all a non-issue because the singularity [the point at which technological changes happen so rapidly, a self-improving artificial intelligence will emerge] will happen around 2045, and then we’ll be integrated with machines and live forever anyway.”

Welcome to heaven.