Real to Reel Ten Classics in Humanist Cinema

UNIVERSAL CITY, CA—Cameras were flashing February 18, 2011, as men and women in elegant tuxedos and beautiful gowns rose to accept their awards for last year’s crop of films. No, it wasn’t the Academy Awards. It was the 19th Annual Movieguide Faith & Values Awards Gala, the self-described “Christian Oscars.” Each year some of Hollywood’s brightest stars are on hand to witness the John Templeton Foundation’s awarding of $100,000 to the film that best “increases man’s love and understanding of God.” (Although, identifying host Kevin Sorbo and presenters Nadia Bjorlin and Eric Martsolf from Days of Our Lives as bright stars might be pushing it.)

So, why don’t humanists have their own film awards? A festival for the rest of us, if you will. How does one clearly define a motion picture genre as humanist? What exactly is a humanist film?

Let’s start with what it’s not. First, and obviously, a humanist film would not assume or celebrate divine intervention, no deus ex machina. This particular plot device, created by the Greeks and literally meaning “god from the machine,” has been used in drama to resolve particularly irresolvable story lines. An actor, portraying a god, might be lowered onto the stage with a crane. Once there, this character magically sets everything right. So Glinda the Good Witch can’t conveniently decide to float down and send Dorothy home at the conclusion of The Wizard of Oz. Opening the relic at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark to unleash the power of God to kill all the Nazis and melt their faces—not acceptable. We should probably also exclude any films in which the hero sacrifices himself or herself for the sake of humanity. We’re not looking to replace Jesus with a different martyr.

So what might a good humanist film be like? I’m thinking of those few films that reject religion and supernaturalism, even peripherally, and that uphold the ideals of reason, ethics, and justice while also celebrating what it is to be human. A humanist film should identify and explore the individual as well as the shared human experience.

Lofty goal, I admit. Nevertheless, after hours of grueling research (mostly me sitting around watching DVDs in my shorts), I now present, in no particular order: THE TEN GREATEST HUMANIST FILMS EVER MADE!

INHERIT THE WIND (1960)

INHERIT THE WIND (1960)

This film, adapted from the play of the same name and based on the Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925, involves two great trial lawyers pitted against each other concerning the crime of teaching evolution in a public school. The scenes between Spencer Tracy and Fredric March, who play the oratory titans based on Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan, respectively, are powerful. But my favorite scenes are those between Tracy and Gene Kelly. Kelly’s character is a wisecracking, big city reporter and an outspoken atheist who seems to take pleasure in confrontation, razzing the locals about religion whenever he can. Tracy’s character, on the other hand, seems uncomfortable discussing religion with strangers, even though he too is a nonbeliever.

This subplot echoes an issue many nontheists grapple with today. Do atheists, like Kelly’s character, become narcissistic cynics whose only pleasure is in irritating the believers? Or do we try to find some other way? You’d think taking on the taboo subject of atheism in 1960 would have been enough for director Stanley Kramer. But he goes beyond that to explore the many different varieties of nonbelief. There’s the science teacher played by Dick York (yes, the Bewitched guy) who has no desire to serve as a test case for the teaching of evolution. And there’s his girlfriend, herself just beginning to question her faith and who also happens to be the preacher’s daughter. It is this examination of other flavors of atheism that makes this film special.

There is one problem with this film—the ending. People who’ve seen it know what I’m talking about. What’s up with that? [SPOILER ALERT:] Tracy picks up On the Origin of Species and the Bible, as if to weigh them, then slaps them together and shrugs. Are we to believe that both should be treated equally or that ultimately there’s no conflict between the two? Can Tracy’s character, who argued so eloquently that evolution should be taught in the classroom, also believe in the word of God? Maybe that’s what makes this such a great humanist film, for it is the complexity of the human being that is so fascinating and so wonderful.

HAROLD AND MAUDE (1971)

Once we accept that there is no God and that we alone are responsible for giving our lives meaning, inevitably nihilism raises its ugly head. Harold (played by Bud Cort) is a young boy of privilege alienated from his rich and overbearing mother. His apparent lack of purpose manifests itself in very bizarre ways. He drives a hearse, refuses to date, and spends his time attending the funerals of strangers. Oh, and he likes to fake his own death.

Enter Maude, an energetic free spirit whose life experiences have left her totally unafraid to live life to its fullest. “Do you pray?” Harold asks her. “No,” she answers, “I communicate.” “With God? Harold asks. “With life,” Maude responds.

Harold can’t help but fall for her. But if you think this sounds like a standard love story, it’s not. Maude, played by the magnificent Ruth Gordon, is some six decades older than Harold. (The thing about humanism is, you have to be open-minded.)

Maude is the perfect guide, offering Harold one lesson after another on how to appreciate life and live it with gusto. There are too many great scenes to list (a number of which involve the septuagenarian peeling out in stolen cars) but one in particular highlights this movie’s moral core. As the two stroll through a field of daises, Harold expresses his desire to escape from life. He comments to Maude that he would like to be a daisy because they’re all the same. Maude is quick to point out how wrong Harold is. “Some are smaller, some are fatter, some grow to the left, some to the right. Some even have lost some petals—all kinds of observable differences. You see Harold,” she goes on, “I feel that much of the world’s sorrow comes from people who are this–” (she holds up a single daisy) “yet allow themselves to be treated–” (here she points to the entire field) “as that.”

I would be remiss in not mentioning the wonderful soundtrack in this motion picture. Much of the film’s rich philosophy is translated through music composed by the legendary Cat Stevens (including “If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out” and “Where Do the Children Play?”) The lyrics of some of the songs could be adopted as anthems for a humanist revolution. If only.

CHOCOLAT (2000)

CHOCOLAT (2000)

Does a movie have to be based completely in reality to be humanist film? Can it contain magic? As long as the magic is of a certain variety and is merely a plot device, not the central message of the film, I think it can. And this film certainly contains the right kind of magic. I’m referring to a type inherent in all the good things that exist on earth—in things like chocolate.

The story of Chocolat is set in a small French village, whose inhibited mayor (played by Alfred Molina) thinks the only way to salvation is through self denial. But a new resident has blown into town, played by Juliette Binoche, bringing with her sweet temptations. In the center of this highly pious hamlet, she plans to open a chocolate shop just before the beginning of Lent.

Trying to live the good life is one of the goals of humanism. Here is a movie that celebrates the things that make us happy: dancing, falling in love, and of course, dessert. Directed by Lasse Hallström, this film teaches us not to abstain from the pleasures that life offers us just because the self-righteous have labeled them indulgent.

One thing that I really liked about this movie is that although the Catholic Church plays an important part in the plot, the church isn’t the antagonist. This is a humanist film you can watch with your religious friends (just make sure they’re not dieting before you invite them over).

AMERICAN BEAUTY (1999)

In my opinion, this quirky treasure could be the gold standard for secular humanist films. It begins with a voice-over in which the main character, Lester Burnham (played by Kevin Spacey), informs the audience that in less than one year he’ll be dead. “In a way, I’m dead already,” he says. Welcome to a world void of self-actualization.

Lester is a middle-aged zombie with an unfulfilling job and a family that no longer loves him. So what is it that turns his life around—pot? Actually it’s the person he’s getting the pot from, Ricky (Wes Bentley), the self-assured but enigmatic teen who’s just moved in next door.

The humanist philosophy has always shared certain overlap with Buddhism, and in this film the video camera-toting drug dealer, Ricky, is definitely the Buddha. He sees beauty in everything around him, even a plastic bag blowing in the wind. His actions and ideas present us with a person at peace—both with himself and the troubled world.

Achieving self-actualization is often misinterpreted as pushing aside those who get in your way. Humanism has likewise been labeled selfish. Here, director Sam Mendes demonstrates how humanism is actually the exact opposite of selfishness. Most of the conflicts in this movie arise because people think their happiness depends on the actions of other people. To get what they want, the characters don’t try to take control of their own lives, but instead try to control the lives of those around them.

That Lester is trapped in this very mindset is illustrated most vividly by an inappropriate infatuation with his teenaged daughter’s friend, Angela (played by Mena Suvari). Lester sees her as a thing, a sex object, and attempts to pursue her as such. But with Ricky’s inspiration, and some outstanding dialogue, Lester discovers a better way, seeing Angela not as an object, but as a human being—as an innocent and vulnerable girl. He learns that happiness can never be achieved through the exploitation of other people. By the end of the film, when asked how he’s doing, Lester’s serene response—“I am great”—is truly sublime. He becomes the Buddha.

MONTY PYTHON’S LIFE OF BRIAN (1979)

What can I say? This film is a masterpiece, a comedy treasure, a tour de force. Now, I understand that there are some people who don’t particularly like Monty Python’s unique brand of humor. But if you can’t resist a good send-up of Christianity, this film is truly not to be missed.

On the day of his birth, Brian’s parents decide to take refuge in the stable next to the baby Jesus. Subsequently, Brian (played by Graham Chapman) is mistaken for the Messiah by the three wise men. This confusion seems to plague the hapless Brian throughout his life as he is thrown into one situation after another in which he is erroneously identified as the son of God. Through all the hilarity and silliness, Life of Brian manages to satirize almost every irrational feature of religion, from how people misinterpret religious messages (“I believe he said, ‘Blessed are the cheese makers.’”) to the absurdity of its many splinter groups (“Judean People’s Front? Fuck off! We’re the People’s Front of Judea!”). The act of blind devotion is appropriately skewered in a scene where Brian encourages a huge crowd of followers to think for themselves:

Brian: Look, you’ve got it all wrong! You don’t need to follow me, you don’t need to follow anybody! You’ve got to think for yourselves! You’re all individuals!

The Crowd (in unison): Yes! We’re all individuals!

Brian: You’re all different!

The Crowd (in unison): Yes, we are all different!

Man in Crowd: I’m not.

Another Man: Shhh!

The philosophy of director Terry Jones is clearly present in a scene where Brian is being chased by a garrison of Roman guards along with his school principle. To escape, he tries to hide among a group of ranting prophets. In order to blend in, he starts to proselytize. What’s supposed to be off-the-cuff babble sounds like a flat-out enunciation of humanist values. This culminates in Brian being led to his crucifixion while a chorus of fellow crucified prisoners happily sing “always look on the bright side of life.” All zaniness aside, the film’s lessons are admirable: take responsibility for your own life and your own happiness. Furthermore, if it doesn’t concern you, and it’s not hurting anyone, mind your own business.

AMADEUS (1984)

Amadeus, which won eight Academy Awards including best picture, is a lesson in the futility of obsession. In truth, this is not the story of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (played by Tom Hulce) but the story of his supposed friend and fellow composer, Antonio Salieri (F. Murray Abraham).

Salieri is both a great lover of music and a devoutly religious man. While most people are too unsophisticated to recognize Mozart’s gift, Salieri recognizes his true genius and, having little innovative talent of his own, begins to question God’s motives. Why would the Lord give him the ability to appreciate this creative master and yet withhold such talents from the more devout Salieri? This sends him into a spiral of divine conspiracy and revenge. The thing is, on some level Salieri’s logic is sound; if one accepts the existence of God, then every one of his conclusions seems rational. Salieri’s father dies, for example, giving the young man the opportunity to attend music school, which he proclaims a miracle. God seems to grant Salieri one wish after another only to snatch them away later, which he comes to see as God playing games.

The greatest insult by far is that the almighty has sent a vulgar child (the mischievous Mozart) to taunt the talentless composer. Why shouldn’t Salieri do everything in his power to oppose God? I’m constantly surprised more people don’t act the way he does. For some reason, believers give God a pass. What they don’t realize is that by quietly denying God’s existence when bad things happen, they’re actually demonstrating how insubstantial their faith really is.

Director Milos Forman and writer Peter Shaffer do a great job of secularizing this highly religious subject. With all the talk of inspiration and faith, God, as an active character, is conspicuously absent. Sure, Salieri might succeed in destroying Mozart and by doing so defeat God himself, but in the end it’s clear that the frustrated composer is only swinging at the wind.

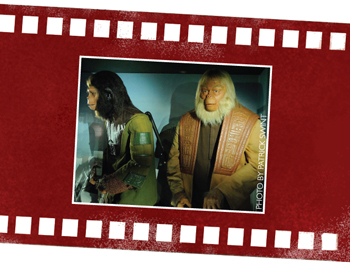

PLANET OF THE APES (1968)

PLANET OF THE APES (1968)

I have a definite soft spot for sci-fi films with heavy-handed social commentary. Add Charlton Heston’s acting, the Statue of Liberty, and talking monkeys and I can’t resist. But what do these elements have to do with humanism? Hidden under the film’s novelty (like Roddy McDowall under all that makeup) lies a film all about humanity. Sure everyone remembers the final scene, where Heston’s character George Taylor falls on the sand upon realizing where he is, but what about the scene in the courtroom where Taylor is put on trial for being human? You can find a thousand parables about humanity in this movie because it attempts to look at the human race through the eyes of another species. Nearly every line has a double meaning, mocking class division, racism, or how Homo sapiens treats other animals.

If you do research you’ll find plenty of commentary on all those subjects, but quite often the analysis ignores the core message in this film, that is Planet of the Apes’ position on science versus religion. Director Franklin Schaffner takes great joy in pointing out that sacred texts (much like history) are written by the victors. By having Heston challenge the old scrolls of ape civilization, he is really asking us to challenge our own sacred books.

The conflict between science and religion is made even clearer through actor Maurice Evans. He portrays Doctor Zaius, the devious orangutan, whose position in the government is not only that of Minister of Science but also Chief Defender of the Faith. You can imagine how well that works out.

DEFENDING YOUR LIFE (1991)

This little-remembered gem, written and directed by Albert Brooks (who also stars), will no doubt be a controversial choice. How can I justify putting a movie that takes place in heaven on the list? Believe me, this is not your daddy’s heaven. In fact it looks a lot like Los Angeles, only really clean.

Imagine a heaven where there is no God, a heaven that was conceived, built, and is run entirely by ordinary people like you and me. Sure these people are a little smarter but, as we all will, they’ve died and in life shared a lot of the same experiences.

For followers of the Abrahamic religions, heaven can end up being an excuse not to do much while we’re alive on earth. Why should you work hard to make a better life for yourself or the people around you if you get all that later in heaven anyway, the idea goes. Defending Your Life turns that idea on its head. The hereafter is the entire reason to live your earthly life to its fullest. If you don’t, you die and the people in “Judgment City” just stick you right back on earth until you get it right.

The idea of defending one’s life therefore has many meanings in the film. Brooks’ character is put on trial and must defend the decisions he’s made. Through flashbacks we see that, while he was alive, he was given opportunities to improve his life, to defend the precious existence he’d been given. Getting it right, the film stresses, doesn’t just mean being good either. It means being brave, being strong, and having the courage to go after what you want in life.

There are plenty of “carpe diem” movies out there, but I especially like this one because it arrives at the idea from a completely different direction. And the others can’t claim Meryl Streep among the cast.

THE FOUNTAINHEAD (1949)

THE FOUNTAINHEAD (1949)

If you’re ever sitting around with your friends talking about humanism, someone will inevitably mention Nietzsche or the objectivists. Ayn Rand’s book, The Fountainhead, is full of it (Nietzscheism, I mean). I might not agree with everything in Rand’s books, but this movie is a bit softer on the whole Übermensch idea. So, it’s a good place to start when talking about the integrity and value of the individual over the tyranny of collectivism.

After humans cast off the shackles of religion, what’s left for our species but to bask in the glory of humanity itself? We are presented with humanism, as if it had slipped on a Superman costume. It is magnificently symbolized by Gary Cooper, hands on hips, standing atop the tallest skyscraper in the world, his shirt blowing in the wind like a cape. I’m not being cynical here. This image is a good thing.

Cooper plays Howard Roark, an architect who refuses to compromise one inch on his designs. If you are an artist or have ever designed anything in your life, you have to love this film. Roark’s mentor uses his last breath to tell him, “The form of a building must follow its function,” before dying. That’s a commitment to ideals I’d like to posses. (I’m planning my last words to be “never buy a beige sofa.”)

The Fountainhead is filled with inspirational scenes and great speeches that rejoice in the individual. Roark’s opposition is nothing less than society itself, a society that rewards the banal, that places mob rule above intellect, a society that is “perishing under an orgy of self-sacrifice.” Roark manages to move forward, to spite all this, whether people agree with him or not, exhibiting integrity as his only banner.

SCHINDLER’S LIST (1993)

I would not have included The Fountainhead in this list if I could not also include this film. In a sense both are the product of a moment in history. Both films arose from the threat (real or imagined) posed by the new ideas of communism. Although Spielberg’s film is a true story, it kind of begins where the cartoon ideals in The Fountainhead leave off.

A self-made industrialist, Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), arrives in town to make his fortune as a war profiteer. As his company grows, he increasingly finds himself relying on the forced labor of Jews to staff his factory. As their lives continually degenerate under Nazi rule, Schindler begins to see his workers less as raw material, a means to an end, and more as individuals—as human beings. Throughout the film the symbol of the individual is juxtaposed against the startling images of the suffering masses. No scene illustrates this more than when the ghettos are being liquidated and Jewish families are being herded onto trains headed for labor camps. At the same time that Spielberg shows us a wide view of the crushing brutality of that moment we are also made to see its effects on the individuals. Schindler can’t help but watch one particular little girl in a red coat (one of only a few times Spielberg chooses to use color in this mostly black and white film.) Like a single small flame, she alone drifts through the wholesale slaughter of hundreds of people.

When he’s told that his workers will be shipped off to Auschwitz, Schindler protests. To save as many people as he can, Schindler puts together a list of laborers who he says are essential for him to continue his work. To be included on the list basically means being rescued from Hitler’s “Final Solution.” The list itself is a symbol of the duality of these ideas. As a whole it represents the suffering of millions during the Holocaust while the individual names are symbolic of the personal suffering of each human being.

Spielberg chooses to end his film by showing us the actual people who were portrayed. This is one of the elements that make this film so powerful. Spielberg doesn’t just allow us to walk out of the theater thinking, “Wow, that was a great movie.” Spielberg wants us to know that these are living, breathing people. It is this focus on the individual that makes this film the masterpiece that it is.

THERE YOU HAVE IT

For those left scratching their heads in astonishment that I omitted a certain humanist masterpiece, I can only say that everyone’s list will vary. For those absolutely incensed that I didn’t include any of the Star Trek films, please see my article “Star Trek Made Me an Atheist” from the July/August 2009 Humanist. And speaking of yours truly, why should I be presenting this list, rather than a select editorial board or esteemed panel of humanist critics? Two reasons—one, when I contacted Paul Kurtz, one of the great lions of humanism, and asked him what his favorite movie is he wrote back, Dude, Where’s My Car? (I might have gotten the email address wrong.) Second, and more importantly, I contend that my list is as important as anyone else’s. The great thing about humanism is that it concerns itself with the individual as much as it does with humanity as a whole. And that’s just what all these movies have in common, a celebration of the single person, as important as the group. In the end these are films that not only have great meaning to me, but are important works of art that have great value for all of society. That’s one guy’s opinion anyway.