Never a Magic Bullet The Personal and Public Dimensions of Gun Ownership and Gun Violence

My father, a volunteer police officer, kept a .44 Magnum under lock and key in the drawer beside his bed. This is the gun made famous by Clint Eastwood in the Dirty Harry films, along with the line: “Go ahead, make my day.” By the age of twelve I had successfully picked the drawer lock. So anytime my mother and father were out of the house I was able to play with this weapon that, according to Homicide Inspector “Dirty” Harry Callahan, “would blow your head clean off.”

Let me take an aside here to stress that my father did all he could to ensure proper gun safety in our household. The guns he owned were locked down and he had taken the time to make sure I knew all the rules of safely handling a gun: keep the safety on, never point a gun at anyone, always treat it as if it were loaded, and so on. For a twelve-year-old, boundaries are meant to be pushed—the rotating cylinder, trigger mechanism, and especially the potential destructive force of this device were endlessly fascinating to my young mind.

Let me take an aside here to stress that my father did all he could to ensure proper gun safety in our household. The guns he owned were locked down and he had taken the time to make sure I knew all the rules of safely handling a gun: keep the safety on, never point a gun at anyone, always treat it as if it were loaded, and so on. For a twelve-year-old, boundaries are meant to be pushed—the rotating cylinder, trigger mechanism, and especially the potential destructive force of this device were endlessly fascinating to my young mind.

These memories came back to me vividly when I recently read news of a four-year-old child in our neighborhood who accidentally killed himself after finding his father’s gun placed in a nightstand drawer, as my father’s had been. My wife and I had our first child last year, and I knew immediately that I had to get rid of the Smith and Wesson I kept in a lockbox up on a shelf in our closet. It’s terrifying for my adult mind to contemplate how my childhood playtime, many times with a sibling or friend present, could have gone horribly wrong with one click.

Getting rid of my gun was a personal choice based on my personal experiences and feelings. I understand that many Americans feel very differently and would be critical of my decision, thinking that the danger of not owning a gun carries far more risk for me and my family. Reasonable people can disagree on this personal decision.

The horrifying murder of twenty young children and six adult staff by a mentally ill man firing a Bushmaster XM-15 at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, on December 14, 2012, followed the murder of twelve in Aurora, Colorado, in July. Before these were the 2009 murder of thirteen people at Fort Hood, Texas, the 2009 murder of thirteen in Binghamton, New York, and the 2007 murder of thirty-two at Virginia Tech. The seeming regularity and intense media coverage of these shootings, combined with the most recent event involving innocent children of such a young age, has pushed the debate over gun control into a fevered pitch in the United States.

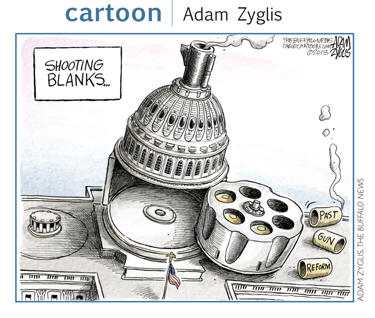

One month after the tragedy, as social networks and online forums still raged with posts from both sides of the debate, President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden unveiled sweeping legislative proposals on gun control. And on January 30 the Senate Judiciary Committee held its first major public hearing on how to combat gun violence.

Personally, I’ve been trying hard to figure out where I stand on the issue of guns in our society. The first step in understanding is to look past the hyperbolic misrepresentations each side of this debate has leveled at the other. While a small minority of gun-toting Americans do appear to stand in direct opposition to humanism, stockpiling firearms in almost eager anticipation of what they believe is the impending collapse of civilization, gun ownership in and of itself does not conflict with humanism. The hunters I’ve known personally, for example, have all been good human beings with a strong appreciation for nature and concern for the environment. If we don’t conserve our natural resources, they reason, there won’t be anywhere to practice our sport.

At the other end of the spectrum, very few gun control proponents are arguing for the federal government to seize all guns, which would deprive some 40 to 47 percent of households of what many Americans feel is a necessary tool for protecting their families. Advocates of gun control are looking for measures that would prevent the mentally ill and criminals from obtaining guns, and put regulations on guns to reduce their lethality. No one argues that the Second Amendment protects the right of individuals to own tanks or rocket launchers. Similarly, gun control proponents are seeking the ideal mean between a gun that can fire ten rounds before reloading and those used at Sandy Hook and Aurora that can fire thirty rounds, or magazines available online that can carry one hundred.

On the rhetorical level of the debate, gun rights’ advocates emphasize the Second Amendment’s “right of the people to keep and bear arms,” while gun control proponents emphasize “a well-regulated militia” as a qualification to the Founders’ intent. Those staunchly supporting gun rights believe it is their civic duty to remain vigilant against the possible rise of tyranny in the United States and quote Thomas Jefferson’s cryptic warning that “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” Gun control advocates note that no cache of firearms is large enough to take on the U.S. government and the largest, best-armed military in the world.

On the factual level of the debate, each side has plenty of statistics to support its case. Gun control advocates are correct when they argue that, according to the FBI, the number of murder victims from firearms in the United States compared to those by beatings is more than ten to one. Gun rights advocates are correct when they point out that Mexico has very strict gun laws, but has a higher firearm homicide rate than the United States per 100,000 people. Gun control advocates are correct that the U.S. homicide rate by firearms is nearly twenty times that of other wealthy countries and that we have the highest gun ownership rate in the world. Gun rights proponents are correct that the Federal Assault Weapons Ban had no discernible effect on crime rates during the decade it was enforced.

On the factual level of the debate, each side has plenty of statistics to support its case. Gun control advocates are correct when they argue that, according to the FBI, the number of murder victims from firearms in the United States compared to those by beatings is more than ten to one. Gun rights advocates are correct when they point out that Mexico has very strict gun laws, but has a higher firearm homicide rate than the United States per 100,000 people. Gun control advocates are correct that the U.S. homicide rate by firearms is nearly twenty times that of other wealthy countries and that we have the highest gun ownership rate in the world. Gun rights proponents are correct that the Federal Assault Weapons Ban had no discernible effect on crime rates during the decade it was enforced.

I myself agree with economist Roger Brinner that “the plural of anecdote is not data,” and these one-dimensional statistics oversimplify an extremely complex issue that encompasses cultural norms, standards of living, and political ecosystems, in addition to regional laws regulating gun ownership. When confronted with an emotionally charged, highly complex issue, I find the clearest understanding can be found with a thorough review of the scientific literature.

Peer-reviewed journal articles have the benefit of looking at various dimensions of an issue in isolation in order to paint a broader picture. What is the suicide rate of gun owners versus non-gun owners? What is the likelihood of a gun owner being shot than a non-gun owner? Is there a correlation between gun ownership and domestic violence? All of these questions are matters of public health, and should be subject to substantial medical research.

The Harvard Injury Control Research Center has a large number of studies correlating gun ownership with increased homicide, suicide, accidental firearm deaths, violent deaths to children, road rage, and other social ills; unfortunately, these studies were almost all conducted by the same small group of researchers. While those studies yield important results, they still need replication by other organizations. A search for “gun violence” on PubMed (a database maintained by the U.S. National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health) yields just over one hundred articles published in the last twenty years. A few of these articles support the finding that a gun in the home increases the risk of being shot, whether it’s suicide, homicide, or accidental. But it’s difficult to build a nuanced public policy position on the issue of gun control without stronger scientific data.

In 1996, Congress stripped the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of funding for research that “may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” In 2010 the NRA successfully lobbied to have restrictions placed on the ability of doctors to gather data about patient gun use into the Affordable Health Care for America Act. In 2012 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was prohibited from spending money “to advocate or promote gun control.” Most egregiously, a 2011 bill signed into law by Florida Gov. Rick Scott made it illegal for doctors in the state to ask patients if they own guns, preventing even pediatricians from asking parents if their guns are stored safely away from children.

More than anything else, we need honest and transparent scientific research on the impact of guns and gun ownership—not only so we can have an informed public discourse on the issue, but so that individuals can make informed personal choices. Preventing doctors and scientists from collecting data on the effects of gun ownership denies us the empirical insight necessary to exercise our Second Amendment rights in a responsible fashion—including the right to choose not to own a gun based on the available empirical evidence.

As a matter of public policy, our society has a responsibility to continue to pursue open, informed debate on the subject, and enable our doctors and scientists to continue researching the public health issue of gun-related injuries. Furthermore, if we can all work toward humanist ideals in our society—where social safety nets ensure the mentally ill get the care they need, elevated standards of living provide all with basic human needs, public education provides people with the insight necessary for rational, peaceful problem-solving, and a stable, altruistic, interdependent civilization provides everyone with a sense of security—then violent crime, which has declined by two-thirds in the United States since 1994, will continue its downward trend.![]()