Building Bridges or Blowing Them Up? Secular Americans and the Future of Humanist Activism

Polls indicate that some interesting shifts are under way in religious life in the United States. The number of people identifying their religion as “none” has crept upward again, now hovering at around 20 percent. At the same time, trust in institutionalized religion is dropping.

Polls indicate that some interesting shifts are under way in religious life in the United States. The number of people identifying their religion as “none” has crept upward again, now hovering at around 20 percent. At the same time, trust in institutionalized religion is dropping.

What might this mean for politics and social change in the United States? David Niose, president of the American Humanist Association (AHA), explores this question and others in his new book, Nonbeliever Nation: The Rise of Secular Americans. In the book’s concluding chapter, “A Secular Future,” Niose discusses the things nonbelievers need to do to be more visible and active in political and public life. He has many good things to say, and I recommend the book to you.

But the road ahead will not always be smooth, straight, or pot-hole free. As secular Americans grow in number, they will be forced to confront an issue that I fear may divide our community: How are we to deal with moderate or liberal religious people? Can they be our allies? Do we want to align with them?

During my travels in the world of organized nonbelief, which span nearly three decades, I have encountered many people who’ve had bad experiences in religious communities. Some were raised in strict fundamentalist homes (Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, and so on) and carry hard memories of verbal or physical abuse. I’ve met former members of faith-healing sects who didn’t get medical treatment when they were sick or in pain, and ex-Jehovah’s Witnesses who recall sitting at home while all of their friends were having fun at a birthday party.

I’ve heard ex-Catholics talk about being harangued by nuns and priests with stories of an everlasting hell. Former fundamentalists have told me tales of ultra-strict upbringings, faith healings that didn’t work, and long church services punctuated by threats of hellfire and damnation.

One thing I don’t hear often are comments like this: “The services at the United Church of Christ have scarred me for life” or “You know, those Quakers really scared the daylights out of me with all of that silence in church.”

My point is, humanists who have bad experiences with religion tend to come from fundamentalist or ultra-orthodox backgrounds. While many humanists who were raised in mainline churches may now find the theology of those communities unpersuasive, they don’t generally report a lot of horror stories.

My talks with moderate and liberal religious believers bear this out. Through my work at Americans United for Separation of Church and State, I’ve met thousands of Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Wiccans, and others who do more than merely embrace religious and philosophical toleration; they also celebrate the range of theological thought in the United States, including the right not to believe in God or espouse an affiliation with a faith tradition.

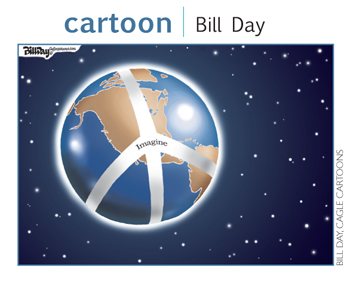

They envision America as a vibrant and open society where the right to believe or not is dictated by individual conscience, not the state. They embrace separation of church and state and a host of other concerns favored by humanists, such as women’s rights, LGBT rights, international cooperation, economic justice, and so on.

We agree on so much—so why aren’t we working together? We are, to some extent. Americans United, for example, is a coalition of believers and nonbelievers that has been very effective,, in part because we’re diverse.

And, of course, humanists already do coalition work. In the nation’s capital, the AHA is involved in coalitions—such as the Coalition Against Religious Discrimination and the National Coalition for Public Education—that include religious groups. If current demographic trends continue, my sense is that we’re going to have to do more coalition work if we want to be serious players on the public policy scene.

At Americans United, we learned long ago that you can only do so much on your own. When we work alongside Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Muslim, and secularist communities, our voice is amplified and our effectiveness rises.

Yet there is a bit of resistance to this among some humanists. Some see all religion as an enemy. The goal of humanism, they argue, is not to work alongside religion but to supplant it. But how likely is this? Is it an effective strategy for success in the policy arena?

Non-religious Americans may be on the upswing, but the United States is far from looking like the secular democracies of Europe, where church attendance has plummeted. Here, humanists will remain a minority for some years to come.

Even in the face of that reality, we can still be more effective in public policy coalitions. The first step is to realize that not all religions are the same. My boss, the Rev. Barry W. Lynn, is a United Church of Christ minister. His tradition represents liberal Christianity. A separate denomination, the Church of Christ, is fundamentalist in approach. One word (ironically, “United”) and a theological gulf as wide as the Grand Canyon separates these two groups. It’s short-sighted to behave as if there’s no difference between the two.

Humanists would feel comfortable living in Lynn’s vision of America because it is based on our shared values of mutual respect, diversity, tolerance, equal rights for all, and, most importantly, a government that remains neutral on matters of theology and doesn’t presume to impose religion on anyone at any time for any reason.

The fundamentalist vision, by contrast, is a nightmarish theocracy where the state not only endorses religion generally but undertakes to enforce the narrow theology espoused by hardline Christian denominations.

The second step—and I concede that this will be controversial to some—is for secular Americans to dial back the rhetoric of religion bashing. Such talk has been a staple of organized nonbelief for decades. It might have been understandable when we were totally marginalized, but as our numbers and political influence grows, we’ll find that it’s doing us no favors. If we want Americans to get interested in what we have to offer, we must define ourselves on the basis of what’s good about humanism, not what’s bad about religion.

Blanket assertions that all religious people are stupid or that mainline faiths are just apologists for fundamentalism (or, worse yet, gateways to it) aren’t only untrue, they’re not helpful. They alienate and insult the millions of Americans who belong to moderate or liberal faith communities, people who share none of the values of politicized fundamentalism.

Humanists have more in common with some believers than we realize. Fundamentalists have no love for liberal Christians. They also often attack non-Christians, especially Pagans, Wiccans, and followers of Eastern religions. Members of these communities are routinely lambasted by the religious right, which labels them a subversive and even dangerous force that is corrosive and seeks to undermine American values. Sound familiar? These folks are not our opponents; they are potential allies. We ought to be working alongside them, not taking potshots because we don’t agree with their theology.

The final step is to realize that mature political and social movements understand the importance of playing nice with others. You work together when you can. There might be occasional areas of disagreement, but as long as there is more overlap than division, you keep the partnership moving forward.

The final step is to realize that mature political and social movements understand the importance of playing nice with others. You work together when you can. There might be occasional areas of disagreement, but as long as there is more overlap than division, you keep the partnership moving forward.

Humanists and other secular Americans may indeed be on the cusp of some great advancements—leaps forward that people who have long been active in this movement might never have thought possible. That won’t happen if we decide our main goal is to tear down all religions—including those that agree with us 90 percent of the time—instead of building up humanism.