The Feminist Caucus of the American Humanist Association A Brief History

In 1977 professional writer Gina Allen realized a disparity in the numbers of women versus men in leadership positions within the American Humanist Association (AHA), of which she was a member. Men and men’s issues predominated, and few women ever received awards from the group. Allen even learned that on membership lists, married women had identities only through their husbands (Mrs. John Doe, not Jane Doe). Realizing the need to address the sexism within, Allen founded the AHA Women’s Caucus and began a campaign to educate AHA members about the need to change sexist behavior. Her first target was gender-biased language (“mankind” instead of “humankind,” for example), which so often put women in a secondary position.

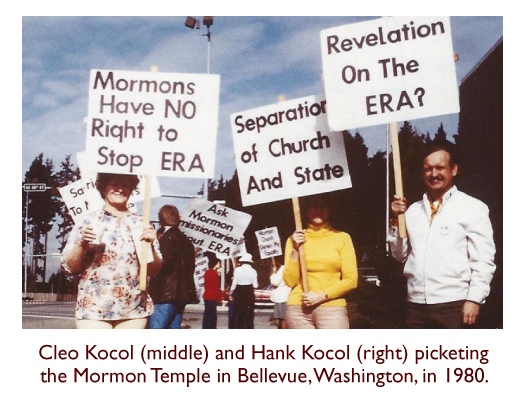

In 1981 I joined the AHA Women’s Caucus at a time when the struggle to pass the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was coming to an end. Having been an active feminist for years, I was one of a number of others who felt that traditional actions weren’t working, and that it was time for radical moves in order to get attention for the cause. In November 1980 I had joined Sonia Johnson, who’d been ousted from the Mormon Church for her involvement in the feminist movement, and nineteen others in chaining ourselves to the Mormon Temple in Bellevue, Washington, thereby barring their leader, Spencer Kimball, from entering. Among the so-called chainers was one man whose name regretfully escapes me. What I do remember is that, when asked later why he’d chained himself with the group of women, he replied: “When my sisters hurt, I hurt.”

In 1981 I joined the AHA Women’s Caucus at a time when the struggle to pass the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was coming to an end. Having been an active feminist for years, I was one of a number of others who felt that traditional actions weren’t working, and that it was time for radical moves in order to get attention for the cause. In November 1980 I had joined Sonia Johnson, who’d been ousted from the Mormon Church for her involvement in the feminist movement, and nineteen others in chaining ourselves to the Mormon Temple in Bellevue, Washington, thereby barring their leader, Spencer Kimball, from entering. Among the so-called chainers was one man whose name regretfully escapes me. What I do remember is that, when asked later why he’d chained himself with the group of women, he replied: “When my sisters hurt, I hurt.”

Still, in the early 1980s men made up the majority of the American Humanist Association, and they were not widely in favor of change. But Allen, thrilled by my militant actions, persisted, and in 1982 I joined her as co-chair of the caucus. She suggested we give Sonia Johnson an award. I agreed, but thought the award should be given at an AHA event and that the name “Women’s Caucus” should be changed to “Feminist Caucus” (FC) to include men. Allen agreed. Incidentally, Johnson was in Illinois leading a fast for the ERA and couldn’t make the 1982 conference at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. Instead, I wrote and performed a one-woman historical show in honor of all women. While it wasn’t universally applauded by the men present, the women felt energized. I subsequently wrote and presented three multi-character shows throughout the United States, including Alaska. At each event I left humanist literature and in those early years gave part of the proceeds to the Feminist Caucus.

The FC became an integral part of all AHA conferences. FC newsletters not only let members know what was going on in the organization but also around the country regarding feminist issues. When the National Organization for Women and other groups marched in Washington, DC, for women’s rights, I led a contingent of feminist humanists carrying a banner that read: “Feminist Caucus, American Humanist Association.” I also represented the AHA at an ecumenical meeting in DC addressing Roe v. Wade. (Incidentally, one of our leading supporters was the late Roy Torcaso who challenged the Maryland law requiring belief in a god to qualify to be a notary public.)

Sonia Johnson was eventually presented with the Humanist Heroine award at an FC event in Washington, DC, in late 1982. A grand collection of feminist activists were in attendance, including the AHA’s Dolly Packard, Billie Khan, and Pat Shockley, along with others like Mary Anne Beale. Sister Maureen Fiedler wrote that she was unable to attend but added that she would have been “especially honored to attend an event sponsored by a group so frequently vilified by the Moral Majority and other right-wing ideologues!”

Other Humanist Heroine awardees followed annually, including abortion rights advocate Patricia Maginnis (who shared the honor with Dr. Ben Munson, who performed illegal abortions prior to 1973); Freedom From Religion Foundation (FFRF) co-founder Anne Nicol Gaylor; Barbara G. Walker; Kate Michelman; Amy Goodman; Kim Gandy; Robin Morgan; Judy Norsigian; and, most recently, anti-war activist and feminist Debra Sweet.

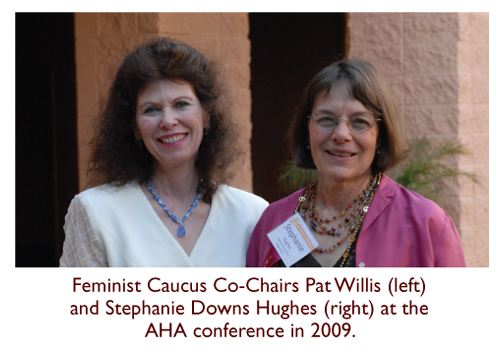

In 1988 peace activist Rosemary Matson and educator Meg Bowman became co-chairs of the AHA Feminist Caucus. Bowman continued carrying the torch for feminist humanism along with FFRF’s Annie Laurie Gaylor into the early 2000s. Pat Willis took over from there, and was joined in 2008 by Stephanie Downs Hughes, who now co-chairs the FC with author and book publisher Zelda Gatuskin.

“Though the female life force is indomitable, there is no question that millennia of second-class status has left a mark on our psyches. (Make that third-class status if God is involved),” Gatuskin said in her first address to the FC as co-chair. “There is nothing selfish about women defending our personhood and demanding the right to speak for ourselves, portray our lives accurately, and protect our physical security. Perhaps it is the single most essential task we have before us as humanists, because obviously we cannot fulfill our true human potential while one half of humanity is suppressed, restricted, and demeaned.”

Acknowledging that such feminist talk “sounds scary” to some, Gatuskin stressed that “we are not at war with men, we are at war with history—a history defined by a patriarchy so tenacious and entrenched it feels almost dangerous to say the word aloud.” Today the Feminist Caucus of the AHA is organizing around two principal efforts: 1) Refocusing on passing the ERA and 2) Promoting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It’s also beginning an experiment to nest leadership in a local/regional FC chapter that will administer the national Feminist Caucus for a period and then pass those duties to another chapter. The FC of the Humanist Society of New Mexico (of which Gatuskin is president) is assuming the initial leadership under this new approach.

Acknowledging that such feminist talk “sounds scary” to some, Gatuskin stressed that “we are not at war with men, we are at war with history—a history defined by a patriarchy so tenacious and entrenched it feels almost dangerous to say the word aloud.” Today the Feminist Caucus of the AHA is organizing around two principal efforts: 1) Refocusing on passing the ERA and 2) Promoting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It’s also beginning an experiment to nest leadership in a local/regional FC chapter that will administer the national Feminist Caucus for a period and then pass those duties to another chapter. The FC of the Humanist Society of New Mexico (of which Gatuskin is president) is assuming the initial leadership under this new approach.

The fact that the FC has, in a sense, come around full circle to the ERA is hardly cause for celebration. Women have made strides toward equal pay, but that’s nothing when you look at how long it took to achieve $0.77 for every man’s dollar. Today, too, many people buy into the notion that women can “have it all” and assume that means they’ve achieved equality. But for every law that helps women there is another that hurts women, and for every man who takes for granted that women are equal to men, there is another who doesn’t feel they’re equal. With right-wing religionists as well as male and female troglodytes in politics waging war against the U.S. female population, the ERA and the AHA Feminist Caucus are needed more than ever.

Visit the AHA website to join the Feminist Caucus.

Cleo Fellers Kocol is a former board member of the American Humanist Association and former chair of the AHA’s Feminist Caucus. In 1988 she was named its Humanist Heroine. A poet and author, her latest novel, The Good Foreigner, takes place in China and the United States during the years 1947 to 1989.